Below you’ll find the main commented Bitcoin source code sections (sorted by section name and filename).

Core

amount.h – Defines the CAmount typedef, implements minimum and maximum valid amount range check.

base58.cpp – The encoding function used for Bitcoin addresses. Base58 removes some potentially ambiguous characters from Base64 so Bitcoin addresses can be written down and passed around without errors.

chainparams.cpp and chainparams.h – Bitcoin Core blockchain parameters. If you fork Bitcoin Core, this is the first file you edit to create a new coin!

consensus/merkle.cpp – Merkle root computation on vectors of hashes and Bitcoin blocks.

dummywallet.cpp – Implements mock Wallet functions that get linked to bitcoind when a wallet-less compilation is requested.

init.cpp – Implements common application startup code. Used by both console and Qt implementations.

noui.cpp – Signal handling subroutines for console-based output and logging.

optional.h – Stub wrapping boost::optional for pre-C++ 17 compilers.

rpc/server.h and rpc/server.cpp – The RPC subsystem which is called from several core components is described here.

uint256.cpp – Here we find the abstract data type for fixed size large unsigned integers. Though the filename contains 256, the 160 bit type for RIPEMD is also defined here.

Qt

qt/bitcoin.cpp – Implements BitcoinApplication

qt/bitcoin.h – Defines the Qt BitcoinApplication main application class.

qt/main.cpp – Short stub that gets the Qt client initialized.

Console

To become familiar with the console initialization, then start here:

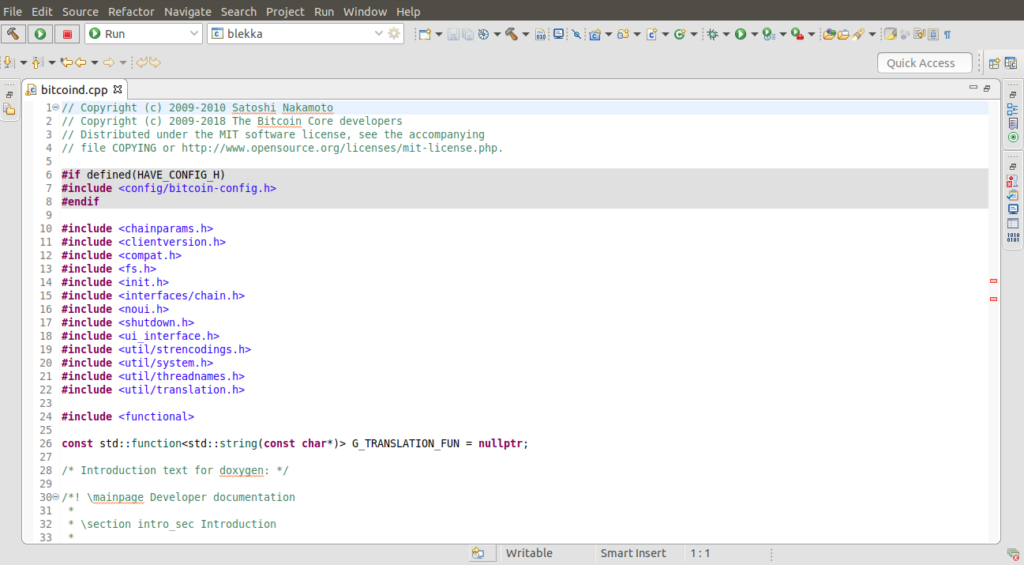

bitcoind.cpp – Implements the Bitcoin daemon / background service.

Both console and Qt initialization routines reach the same subroutine in init.cpp.

—===—

Now for the long story – The details on how I approached the source tree:

Introduction

For a while now I’ve wanted to dig deeper into the inner workings of Bitcoin.

Although I tinkered a lot with Dogecoin and Litecoin source over 5 years ago, I realize they were just forks of the original Bitcoin Core source tree – not the origintal. For a long time I also didn’t trust any Bitcoin Core binaries from the WWW, so I built my own by cloning the Github repository. But being familiar with the build process, and actually knowing how the code works are very different things.

So I decided it was time to become familiar with the magic that makes the king of cryptocurrencies tick.

I’m a big fan of Richard Feynman’s learning technique. And one of the ideas that make Feynman’s method so efficient is to share what you’re studying with others. Try to explain the concepts to someone and you’ll usually run into several aspects of it that you need to clarify. Explaining how something works is, thus, a great way to learn!

In this series of articles I’ll share my Bitcoin source code learning journey with you.

I’ll write the articles as I go, so they’re not too meticulously planned nor heavily edited later. It’s supposed to be a bit experimental and I may make mistakes along the way, though I’ll do my best to correct them.

Strategy

First I had to decide where to start.

The Bitcoin source has become a large software project by now. So the first thing I thought of was to start with the original Satoshi code from 2009 and progress from there.

I took a look at the legacy code and noticed that so much has changed since. I figured that these articles might become too confusing if I must keep referencing back and forth between current and historic code.

So I’ll start with present day source code instead. Since we’re gonna do this, let’s do it the hard way! The main advantage to this approach is, if we’re successful, we’ll gain a clear understanding of the most recent developments like dandelion, segregated witness and so on. The main disadvantage is the steeper learning curve. Bitcoin currently has 21,306 commits in its history. A lot has changed since the 2009 Windows-only release from Satoshi Nakamoto himself.

To progress through the code I’ve decided on the following policy:

- Identify relevant entry points, such as int main() or library equivalents;

- Comment the code found under the entry point;

- Follow the call stack from there;

- Prioritize the discussion based on perceived relevance.

By doing this we follow the natural path, trying to mimic the OS running the program itself.

Of course, Bitcoin Core is a large software base and prioritization is required, otherwise this project might never end. Not all functions and variables will be commented on, especially since a lot of the code comes from libraries like Qt, STL, boost and so on.

So a helper function that was likely refactored out of a bigger function might not be immediately approached while the main trunk would receive our attention.

I hope this works!

Tools

I use Linux exclusively on all my PC’s. I fried a Samsung CRT monitor in 1996 trying to get Slackware Linux’s XWindows server to run, so for me it’s a matter of honoring my monitor’s sacrifice to only use Linux now that L[CE]D screens work out of the box with most modern distros.

I’ve imported the full Bitcoin Core repository into Eclipse CDT. I was once a vim and Emacs maximalist but today I appreciate the software bloat in all its glory. I’ve come to like GUIs.

After setting all the library paths right, the Eclipse indexer did its job and most variables, #includes, methods and classes became control-clickable. This allows me to navigate the source very easily.

Another advantage of using a “heavy full featured” IDE like Eclipse (or Jetbrains CLion if you prefer) is being able to easily find all references to any part of the source code. Want to know every source file that references a variable? No problem, just highlight it and select Source -> References from the context menu. It’s smart enough to tell class names from constructors (same spelling) and to find the correct version of overloaded methods. It also allows me to use a web browser-like feature where it takes me to the last control-clicked point. It’s kinda like unwinding the FILO stack trace and very useful when you’re deeply nested in the call stack.

Other than Eclipse, I’ll be using the command line facilities that come with every Linux box. grep is our friend, along with find, perl and so forth.

How’s this different from the Bitcointalk thread?

If you search Bitcointalk.org for “Satoshi Client Operation” you’ll find several helpful posts by bitrick.

How is this walkthrough different from that one?

First of all, I’m writing this 8 years after the Bitcointalk threads. So the code we’ll comment here, and the whole context around Bitcoin today, has significant differences. The GUI client has moved to Qt, people are not mining using their CPU anymore and so on.

Secondly, I plan on posting actual code chunks to explain them, instead of English pseudo-code. There’s nothing wrong with pseudo-code BTW, it’s just a different approach.

I do recommend you read the Bitcointalk threads as well so you get an idea about how the first Satoshi client worked. It was a Windows-only client initially which was later ported to all (or most) platforms.

Organization

In principle, each article will cover one relevant source code file or header.

Some source or header files are too simple to warrant their own article, so they may be discussed in the same article as other code.

For example, if ACME.h definitions are only used in ACME.cpp, then ACME.h will likely be discussed along with the main article.

Notes

This source code study began with Bitcoin Core version 0.18.99 (August, 2019). I’ll update the posts as I catch up with future changes.

Throughout this series, all source file paths are assumed relative to the Bitcoin Core src/ subdirectory. Every time I mention a file I’ll include the correct directory prefix relative to src/

I built Bitcoin Core once before starting to navigate the code so that config/bitcoin-config.h would be generated as well as the Qt user interface files.

Although I won’t go into the Qt specifics much, Eclipse showed too many broken references until the Qt files where generated by the build process (e.g. files generated by uic – the Qt User Interface Compiler). I’ll comment on the necessary bits of Qt in the context of Bitcoin Core.

In some posts I’ve commented the code directly, note the lines beginning with “>”.

On others I’ve picked specific snippets to comment within the post text. These two styles can vary, depending on how dense the code is. Sometimes it’s best to skip boilerplate and comment on some specific excerpt. In these cases I’ll pick the code to comment. When the code is very dense, I’ll cite it verbatim and comment within it.

I’ve created a category for this series of posts here : Bitcoin Source Code.

From there you can follow along and check out the most recent post in this series in reverse date order.

What next?

This article has been a brief intro to our journey into the center of Bitcoin.

We start our adventure in the qt/main.cpp source file

(Note: This is how this project started in August of 2019, so I left this note here for historical reasons. Today you may start reading from any of the source files.)

The Qt startup and initialization ends at qt/bitcoin.cpp after which there’ll be a reactive system in place listening to Bitcoin network and user events.

Thanks!

I hope you enjoy these posts as much as I enjoyed delving into one of the most successful (and fun) open source projects ever!